A review of the implications of the TTIP for our food security.

A review of the implications of the TTIP for our food security.

Javier Guzmán and Ferran García, VSF Spain – Justicia Alimentaria Global

The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) is a dream come true: the dream of big agribusiness corporations. For the rest of the society is a nightmare. We need to wake up and leave behind this nightmare, as if it was just a bad night.

Agribusiness corporations have been litigating for years in the World Trade Organization against various European regulations that protect some key elements of our food security. It seems that finally the time has come for their problems to be solved. Indeed, they put their negotiators working as government representatives between the United States and the European Union. Their aim is to get a trade agreement between the two regions, which – unlike other treaties already signed worldwide – is not intended to “open” the borders to US food, but to “open” the European agri-food regulatory bodies.

As previously admitted by officials from both sides, the main objective of TTIP is not to encourage trade by eliminating tariffs between the EU and the US (currently tariffs are so low that can be barely reduced further). Its main purpose is to eliminate those regulatory barriers that limit the potential benefits of transnational corporations on both sides of the Atlantic. The problem is that these barriers are actually some of our most valuable regulations on social rights and the environment, including labour rights, food safety standards, restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs), regulations on the use of toxic chemicals, laws of privacy protection on the Internet and even the new guarantee system in the banking sector introduced to prevent another financial crisis like that of 2008. In other words, TTIP is a kind of “treaty bus” in which are traveling some of the regulations that most protect citizens and the environment.

Concerning the agri-food sector, the regulations under negotiation determine how food is produced, how it is labelled, how it is sold, how its safety is assessed and how inspections take place. There couldn’t be more at stake!

Tariffs are not barriers

If we analyse tariffs on bilateral agricultural trade between the US and the EU, we see that, in fact, tariffs have just decreased in the last decades without any major trade agreement. The average agricultural tariff for EU products in the US decreased in six years from 9.9% to 6.6%; while in the EU it has risen from 19.1% to 12.8%. To understand the extent of this data, we just need to say that the average agricultural tariff worldwide is 60%.

If the big agribusiness corporations want, through the TTIP, that a food item produced, processed and marketed in the US can be immediately and automatically sold in the EU and vice versa, then the problem is not on tariffs. Where is it then? In the so-called “non-tariff measures” or NTM in the jargon of the WTO. That is, the laws, regulations and policies of a country affecting food products, which are different from those of another country.

And here is the root of all, because in reality the regulatory frameworks affecting key elements of production, marketing, labeling and food inspection, are radically different between the US and the EU. So how will trade negotiators of the US government and the European Commission resolve these differences between the two systems of regulation?

Don’t worry, they have it clear! To do so, there are two key elements within TTIP negotiations. One relates to a tool and the other to a structure. The tool is Regulatory Harmonization, which states that, between the two standards, it will be chosen the less demanding one for corporations (that is, at the same time, the less protective for the citizens). The structure is the Regulatory Cooperation Council (RCC), and everything suggests that that is the real focus of the TTIP strategy.

The differences

There is an extensive list of differences between the norms on health and food safety between the EU and the US, and we can highlight some of the most important.

Food irradiation is one of them. Irradiation is based on the exposition of foodstuffs to ionizing radiation: generally high energy electrons or electromagnetic waves (gamma or X rays). I

t is just not a “simple food preservation process”, as it is usually called by the food industry. To get a quick idea, the average dose of food irradiation (wherever it is allowed) is 10 kGy (10,000 Grays). To understand this figure we can compare it with an x-ray (1 milligray) or a tomography (0.01 / 0.03 Grays); or say that we just need to expose the skin to an irradiation of 10 Grays to permanently lose hair; or also that 8 Grays reaching a woman’s ovaries are enough to cause infertility. In radiotherapy, finally, the maximum dose used is 80 Grays.

This treatment is permitted in the US for almost all foods, while in the EU it is only authorized for dried aromatic herbs, spices and vegetable seasonings (albeit each member state is free to add new foods to the list). We must remember that this is particularly worrying for consumers because irradiation can form toxic and carcinogenic substances. Irradiation produces free radicals and other byproducts. Very few of these chemicals have been adequately studied on their toxicity effects to

health. Additionally, irradiated foodstuffs are not properly labeled, and consumer’s right to choose with sufficient information is not ensured. Finally, it is known that irradiation reduces the nutritional value of food. For example, it reduces food vitamin content: vitamin E can be reduced by 25% after irradiation and vitamin C between 5 and 10%.

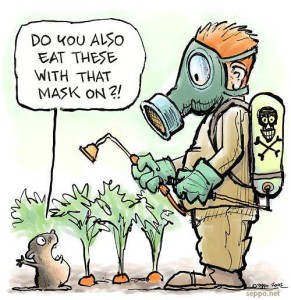

Another difference between the two regulations on both sides of the Atlantic is the list of authorized pesticides. This point makes extremely clear that the main aim of TTIP is precisely to amend the laws. Among the many differences between the legislations on pesticides, the two most important relate to: the large amount of allowed hazardous pesticides in the US that are banned in the EU; and the different levels of residues of these substances that are allowed in the food sold to consumers in the United States compared to the EU. The so-called Maximum Residue Levels, are indeed much stricter in the EU than the US.

Another difference between the two regulations on both sides of the Atlantic is the list of authorized pesticides. This point makes extremely clear that the main aim of TTIP is precisely to amend the laws. Among the many differences between the legislations on pesticides, the two most important relate to: the large amount of allowed hazardous pesticides in the US that are banned in the EU; and the different levels of residues of these substances that are allowed in the food sold to consumers in the United States compared to the EU. The so-called Maximum Residue Levels, are indeed much stricter in the EU than the US.

This issue is not a minor one, as these products have by definition a high biocidal activity and can

cause negative effects on human health and the environment. Moreover, in many cases, they have a high persistence in the environment so that their effects continue on the long term. Consumers are fully aware that they are high-risk substances, as demonstrated by data from the last Eurobarometer dedicated to food-related risks, which indicate that 66% of the Spaniards are somewhat or very concerned about the presence of pesticide residues in food. And a study by the Food Marketing Institute detected that 72% of respondents considered it a major threat to health.

Between the two regulatory systems on pesticides, those that best protects citizens is certainly the European one, which – far from being ideal – is somehow better than the US. We say ‘far from being ideal’ because, for example, each year more than 40,000 tons of pesticides are used (only considering the amount of active ingredient) in Spain, and this intensive use continues to generate complaints about the effects on human health and the environment. For example, a report by researchers at the University of Valencia and the Polytechnic University of Valencia, found 23 different pesticides in various sections of the river Júcar (eastern Spain), including some banned ones.

In The European Union the evaluation, marketing and use of pesticides (herbicides, insec

ticides, fungicides, etc.) is strictly regulated. The EU legislation sets out a procedure for risk assessment and authorization for active substances and products containing them. In order to allow their marketing it is necessary to demonstrate the safety of each active substance from the point of view of human health, including residues in the food chain, animal health and the environment. The industry is responsible to provide data showing that a substance can be used without risk to human health and the environment.

By contrast, in the US, chemical safety is regulated by the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 (TSCA). In contrast to the European process, which reviews all the “old and new” substances, the TSCA provides a series of acquired rights to thousands of chemicals. As an example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has required safety tests on only 200 of the 80,000 chemicals in commerce. Another fundamental difference is that in the US a full risk assessment is required to the government authorities which, in practice, put the responsibility and the burden of showing that a substance is not harmful for the people or the environment on the shoulders of the administration, rather than the industry. This has severe practical implications that ultimately translate into a lot of pesticides freely circulating on the US market without having the sufficient certainty that they pose no risk to health or to the environment.

The RCC

These are just two examples of what lies behind the main objective of this “standards harmonization treaty”, which in practice means devaluating the current European guarantee system, to favor the interests of large corporations. But as we said, the real danger of this agreement lies in the new decision-making structure that is to be introduced in the EU.

Aspects such as GMOs, hormone-treated livestock production or the authorization of pesticides classified as dangerous are what we might call “alert issues”, issues that, when touched, are almost automaticly rejected by the citizenship.

This obviously is well known by both industry and trade negotiators. If it comes to light an agreement authorizing the marketing and the non-labeling of GMOs, or the cattle fattening with estradiol implants, or the free use of pesticides with health risk, then the corporate dream is over. For that reason, disclosing details of the negotiations and presenting it as what it is, a huge deregulatory package, a bus in which are travelling regulations that are going to be tumbled down and make it looking like an accident, could be politically dangerous for negotiators, corporations and, indirectly, the governments that support it, as it could lead to a rejection of the whole package by the citizens and even national parliaments.

Corporate lobby groups on both sides of the Atlantic and their political representatives are well aware of the political difficulties of this type of agreements. They were facing a dilemma. And which answer has been found? The answer is called “regulatory cooperation“. Which translates to “we change just a few things now, but we leave all ready to allow changing the rules on a later stage, slowly, in the dark and alone”.

The Agreement and the Regulatory Cooperation Clause designed a complex framework that will allow taking decisions without real public control and with the doors open to the business lobby. The companies will participate from the very beginning of the process, well before any public and democratic debate, and will have an excellent opportunity to get rid of all the initiatives aiming to improve our food standards or protect consumers. In essence, the proposal would allow business groups to “co-writing” the laws.

Our health is just an obstacle to their profits, and we shall hurry up!

This article is an extract of the Report “TTIPex, borrando derechos“ by VSF Spain – Justicia Alimentaria Gloobal.

The original article – in Spanish – has been published by El País: La insoportable molestia de nuestra salud.